from left: Dr. Frim, Emmanuel Nelson, Noah Johnson (rear), Antonio Pineda, Rod Marco, Bruce Beardsley, Bill Korson

from left:Dr. Frim, 1st place winner Noah Johnson, Rod Marco, Bruce Beardsley

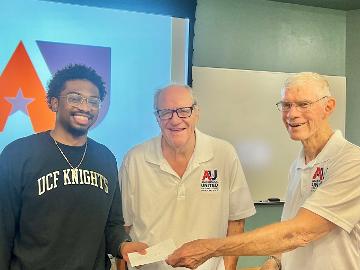

2nd place wiiner Emmanuel Nelson, Rod Marco and Bruce Beardsley

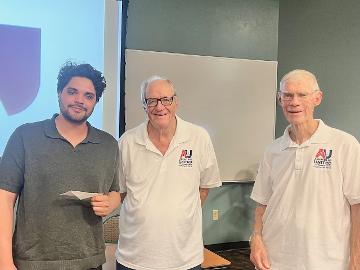

3rd place winner Antonio Pineda, Rod Marco, Bruce Beardsley

To properly evaluate the distinction between education and indoctrination first requires that we clearly define the intentions of each. By understanding the intended outcomes of education and indoctrination, and the tactics employed to arrive at those ends, we can better understand what makes the separation of church and state so important to a stable democracy.

When people think of a public education, they think of subjects like history, science, literature, and math. The purpose of teaching such subjects is to produce well-rounded citizens, knowledgeable of their country’s trials, tribulations, and fundamental tenets, knowledge of some major scientific discoveries (like Isaac Newton’s discovery of gravity or the Copernican Revolution), a familiarity with some culturally significant works of art, and a solid grounding in basic arithmetic and logical thinking. A good education will often include competing viewpoints of historical events and opposing theories of science, chemistry, and astronomy, and allow students the chance to discuss and debate these alternatives amongst themselves.

By allowing each child a chance to explore and learn from a wide range of disciplines, education fosters within them a capability to learn and a willingness to question. It provides them with the seedlings of curiosity that they will later draw from when choosing their own professions. Thus, the central purpose of education is not just to transfer knowledge, but to develop skills of rationality, judgement, and intellectual maturity that will enable citizens to discern fact from fiction themselves, rather than blindly accepting whatever they are told. In short, education is about cultivating an ability for self-rule. A democracy is sure to fail if its citizens do not possess the necessary means to make informed decisions, a worthy intellect being chief among them. In the words of Horace Mann, first secretary of the Massachusetts State Board of Education: “With universal suffrage, there must be universal elevation of character, intellectual and moral, or there will be universal mismanagement and calamity” (Mann, 1842).

Indoctrination, on the other hand, is the teaching of the superiority of one specific viewpoint over another, be it ideologies like Christianity and Classical Liberalism or principles like freedom of speech and freedom of religion. In this sense, we can understand indoctrination—loaded as the term has become in contemporary discourse—as an inextricable part of any education, as all forms of education invariably set out to teach some sort of principles or ideology. For instance, a sound education, as I argue it, would still be advocating in favor of reason, religious toleration, and self-rule.

However, what separates indoctrination from education is the goals they set out to achieve. While education strives to bestow each citizen with a reasoning mind and a resistance to coercive propaganda in conjunction with its particular set of principles, indoctrination is concerned only with the latter—convincing people to believe one ideology or set of principles over another. A successful education is marked by a student’s ability to make decisions rationally and in accord with their own best interests, while the success of indoctrination is marked solely by an unquestioning fealty to one set of principles.

Teaching Religion v. Teaching About Religion

Having set out in detail the distinction between education and indoctrination, we may now address the second question of this essay: Where does religion fall between these two options? I contend that it may go either way, depending on whether the education is concerned with teaching religion or teaching about religion. By “teaching about religion” I understand the process whereby students are taught the historical origins and significance of various major world religions, their influence in the modern day, their differences, various principles, and so on. Understanding what religion is, what it means to people, and what it has meant to them in the past does not constitute indoctrination. It’s not as if advocating for the separation of Church & State means pretending religion does not exist, nor is it a stance against religion. It just means that under the law no one religion would be preferred over any other, whether in education or in politics.

By “teaching religion” I understand the process whereby students are taught to value one religion above all others—a clear case of indoctrination. This is exactly what certain political figures in this country intend to bring about when they talk about “bringing back prayer to our schools.” In Engel v. Vitale (1962), prayer was ruled to be unconstitutional within public schools precisely because they were not as “non-denominational” as its advocates proclaimed. On the contrary, such prayers were explicitly Christian in nature, and were opposed by Jews and atheists alike. Thus, to advocate that we “bring back” prayer to schools is indisputably an argument in favor of one particular religion, and threatens to dissolve the distinction between Church and State entirely.

Conclusion

For the State to endorse a specific religion and teach it in schools thus flies directly in the face of this nation’s first amendment, which explicitly states that there be no established religion (U.S. Const. amend. I). Christian Nationalists often refer to the clause that follows directly after, that the State shall also not prohibit “the free expression thereof,” and use that to make the argument that being prohibited from religious activity during school violates their freedom to religion. However, freedom to religion falls apart without its other half: freedom from religion. If Christians truly desire prayer to be restored to public schools, alongside the inclusion of religious chaplains, while still upholding Constitutional law, they would have to accept the Satanic Temple’s demands to have their own chaplains admitted into public schools, along with any other religious organization who desired those same privileges. Otherwise, the government would be blatantly favoring one religion over all the others, and our religious freedoms would be completely overtaken by a Christian theocracy. Thus, it is imperative that such encroachments of religion upon our public education systems be met with firm opposition—our democracy cannot survive without it.

Emmanuel Nelson

Education or Indoctrination? The Role of Religion in Public Schools

As a 23-year old college student, faith has always been a big part of my life. Growing up in the Church, I saw how much it shaped not only my spirituality but also my education, culture, and activism. Being part of the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee) has given me a strong foundation in my beliefs, and I’ve always valued how faith can be a source of guidance and strength. But at the same time, I understand that public education is meant for everyone, regardless of religious background. That’s where things get complicated. There’s a fine line between education and indoctrination when it comes to religion in schools.

Education encourages critical thinking, asking questions, and looking at different perspectives, while indoctrination enforces one belief system as absolute truth. The question is, how should religion be handled in public education? Should it be included at all? And if so, how do we make sure it’s done in a way that respects everyone’s rights?

Religion has always been tied to education in America. Some of the first schools in this country were started by churches, and many of the oldest universities: Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, were originally religious institutions (Marsden, 1994). Even today, private religious schools carry on that tradition. But public schools are different because they serve students of all backgrounds. That’s why the First Amendment is so important. It says that the government can’t establish a

religion (the Establishment Clause) but also can’t prevent people from practicing their faith (the Free Exercise Clause) (U.S. Const. amend. I). That means public schools have to balance: they can’t push religion, but they also shouldn’t silence students who express their faith. I do believe religion should be included in education, but in a way that teaches about it rather than promoting a specific belief system. Teaching world religions in history or social studies classes can help students understand different cultures and perspectives. For example, discussing how Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Christian faith influenced the Civil Rights Movement isn’t about pushing Christianity, it’s about recognizing the role faith played in history (Branch, 1988).

But if a teacher starts telling students that Christianity is the only true religion or discourages students from their own beliefs, that’s indoctrination.

A big part of this debate is understanding the difference between teaching about religion and teaching religion. Teaching about religion means looking at different faiths from a historical or cultural perspective, while teaching religion means trying to make students believe in a certain doctrine. That’s where public schools have to be careful. The Black church has a long history of being involved in education, especially during times when Black students were denied equal access to schooling. Churches stepped up to provide education when the government wouldn’t

(Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). Even today, churches in Black communities fund scholarships, mentor students, and create safe spaces for kids in struggling school districts. So faith and education have always been connected for people like me. But that doesn’t mean public schools should be preaching. Faith should be a personal choice, not something forced in a classroom.

That brings up another question: should teachers be allowed to share their own religious views? This is tricky because teachers are people too, and many have strong faith backgrounds. If a teacher simply mentions their beliefs in a way that relates to history or culture, that’s one thing. But if they start preaching or pushing their faith onto students, that’s a problem. Imagine a teacher telling a classroom full of kids, “Only Christians go to heaven.” That would immediately make non-Christian students feel excluded or pressured. At the same time, students should be free to express their beliefs. If a student wants to write an essay about how their faith helped them through a tough time, they should be able to. Schools shouldn’t silence faith, but they also shouldn’t promote one belief system over another. In the Bible Jesus says, “Behold, I stand at the door, and knock: if any man hear my voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me.” Revelation 3:20 KJV. As a Christian I believe that we should not

force our beliefs , but believe in and guide people to a relationship with God.

There have been major Supreme Court cases that have shaped how religion is handled in public schools. Engel v. Vitale (1962) ruled that public schools can’t require students to say prayers, even if the prayers are non-denominational (Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421, 1962). Abington School District v. Schempp (1963) decided that schools can’t force students to read the Bible in class. But that doesn’t mean the Bible can’t be studied, it just has to be for historical or literary purposes, not religious instruction (Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 1963).

What I’ve noticed, though, is that religion seems to come up in schools more when it’s Christianity. When students want to wear a cross necklace or say “Merry Christmas,”. But when Muslim students want a prayer space or Jewish students want time off for holidays, people are quick to say, “Keep religion out of schools.” That’s why this conversation is so important, if schools make space for one religion, they have to make space for all. Otherwise, they’re promoting one faith over another, which goes against the Constitution.

Another issue that comes up is how age and maturity factor into this conversation. Religion in education affects elementary school students differently than it does high school or college students. Younger kids are more impressionable, and if a teacher presents religious ideas as fact, those students might not have the critical thinking skills to question them. In high school and college, students are usually better equipped to discuss different religious perspectives without feeling like they’re being forced into believing one way or another. That’s why world religion courses in high school and college can be valuable they expose students to different faiths

without trying to convert them.

It’s also important to recognize that religion and morality are not the same thing. Some people

assume that if you take religion out of schools, you take morality out too. But public schools can teach ethics without basing them on any one religious doctrine. Schools can teach students about honesty, kindness, justice, and respect without tying those values to a specific religious text. After all, some people who aren’t religious still live by strong moral principles.

At the end of the day, education is about learning, not forcing beliefs. Public schools should teach about religion in a way that helps students understand the world, but they shouldn’t be in the business of pushing one faith over another. Students should be able to express their beliefs, teachers should remain neutral, and schools should focus on knowledge rather than indoctrination. That’s the best way to ensure that public education stays fair and respectful for everyone, no matter what they believe.

Antonio Pineda -

Education, Indoctrination, & The American Tradition

“Render to Cæsar the things that are Cæsar's, and to God the things that are God's.” Mark 12: 17 The breath of God whispered truths into the ears of our forefathers: Man’s freedom is his greatest gift and gravest burden. Because man is subjected to the persistent, never-ending burden of choice—of free will—his morality is inseparably tied to the responsible use of his freedom. Therefore, liberty is not merely granted but entrusted, and its misuse threatens that which makes

man “human”—as the corruption of liberty inversely corresponds with the well-being of personal sovereignty and the collective freedom of a people. Man, then, must harbor a healthy fear for the freedom that courses through his veins because within it moves a blood of inherent fallibility—a temptation for evil, for tyranny. In this sense, the breath of life divinely ordains man and burdens him with the responsibility to properly aim his will, to properly place his faith, and to humble himself before this reality.

Revolutions, however, beget the shedding of blood and tears—the American Revolution, while radical, declared an equally healing truth: All men are created equal, and in this equality, they are bound to each other because of the shared burden of freedom. It is in humility that all men can truly recognize their natural equality as torrents of blood on a blank, white canvas of snow. And like the winter’s sweeping gusts of cold, honest winds, the breath of God whispered about man’s need for self-aware, self-actualizing humility. It reveals with it an obligation to

himself and to others. It demonstrates that, fixed within all of men’s hearts, there is an innately placed moral compass where true north remains as distant as they are aimless. The question then becomes, where should a man aim his freedom, and where must he place his faith? He must anchor his freedom and faith in a tradition capable of reconciling the damning nature of his freedom and the moral necessity of his humility.

This question—where man must place his faith and aim his freedom—extends far beyond the individual’s personal obligations and into the institutions that shape the society in which he lives—most notably, the halls of higher education. The line between education and indoctrination is drawn not in whether our religious history is discussed but in how it is engaged. Education is the open exploration of ideas, history, and truth-seeking; indoctrination is the rigid imposition of belief without room for dissent or critical thought. Education should not be the blind disassociation with the bloody history of man—for this is indoctrination in another, dimly lit, amnesiac light. It must balance the deeply religious history of the nation—of Western civilization itself—with the underlying revelatory principle that all men are equally free to choose their participation. To deny students an understanding of religion is to deny their blood, to deprive them of the full scope of their inherited tradition. Religion, after all, has shaped the very liberties that allow for its critique. Blood has been spilled to afford us costly revelations—epiphanies enshrined and encoded into law. In this understanding, our founding fathers—albeit deeply flawed—were lent an infinite wisdom to declare, first and foremost, the most fundamental of the

rights of men: Freedom of Expression. For example, The First Amendment of the U.S.

Constitution inadvertently affirms a delicate balance by establishing both the protection of religious practice and the prohibition of governmental religious sponsorship. This balance is the backbone of the American tradition and its unrelenting lean, the responsibility of every individual. The cyclical nature of the dialogue surrounding this particular balance underscores the necessity of the conversation. While man frequently falls to the whims of his will, tilting his

society and nation one way or the other, a tradition marked by humility can reign him in.

Landmark Supreme Court cases, such as Engel v. Vitale (1962), have also reinforced that public institutions must not impose religious doctrine or erase the study of religion’s influence on civilization (Facts and Case Summary - Engel V. Vitale, n.d.). The distinction, then, is not whether religion should be included in education but how it should be included. To teach about religion is to educate; to forcibly teach religion is to indoctrinate. The former presents religion as a historical, philosophical, and ethical force, while the latter demands allegiance. The former nurtures critical thought; the latter suppresses it.

It is, therefore, not the role of educators to impose their personal beliefs but to be the

guardians of the free flow of thought, faith, and a humble American Tradition. They must foster an environment of intellectual invitation over forceful imposition. And so, in this pursuit of knowledge, let the lecture hall become a forum of scholarly inquiry, not a pulpit of a decree. Let the old bricks of higher education host a past that informs the future—where a tradition is emboldened and strengthened—where freedom is both honored and understood, and where man, burdened with choice, finds humility in his search for truth. American students and educators alike must bear the crown of thorns that history has placed upon them, clear their vision of its

blood, and recognize that the very impulse driving them toward absolute separation is the same ambition that seeks to claim the throne for itself. Humility is the bottled cure for those drunk on Kool-Aid, religious and secular flavors alike. Educational institutions are solemnly responsible for preserving and upholding this tradition while ensuring they remain factories of the cure, lest they become factories of indoctrination.